This week, the workshop session was divided into four teams to work on data collection based on the provided scenarios. My team, called the Digital Media Team (basic, I know, but it worked for us), chose the following scenario:

Scenario 1: Student-led Data Collection

You are part of a student-led community group called Campus Connect Coalition, who are working to improve the student experience. Their website* reads:

"Campus Connect Coalition is a student-driven organisation dedicated to enhancing the campus experience through collaboration, advocacy, and community engagement. We work to bridge the gap between students, faculty, and administration, ensuring that student voices are heard and valued. By gathering insights, hosting open forums, and advocating for positive changes, we aim to improve university life in areas like academics, resources, and social inclusion. Our goal is to create a more inclusive, supportive, and engaging campus environment for all students."

Your task is to collect and analyse data that will help the group understand the student experience.

(Scenario provided by Dr. Holly Steel, 2024)

Before deciding on this scenario, we discussed and evaluated all three options provided, especially their limitations. Our biggest concern was whether the dataset for each scenario would be difficult to collect. The other two options were focused on “digital engagement” and an open-ended exploration of “the social world.” Like many students, we shy away from abstract topics that are open to varied interpretations, such as “the social world.” The scenario involving university-led data collection was considered too challenging because of access issues and the reliance on institutional cooperation.

Apparently, student experience is one that is omnipresent and easily accessible, with data available through both direct and indirect means.

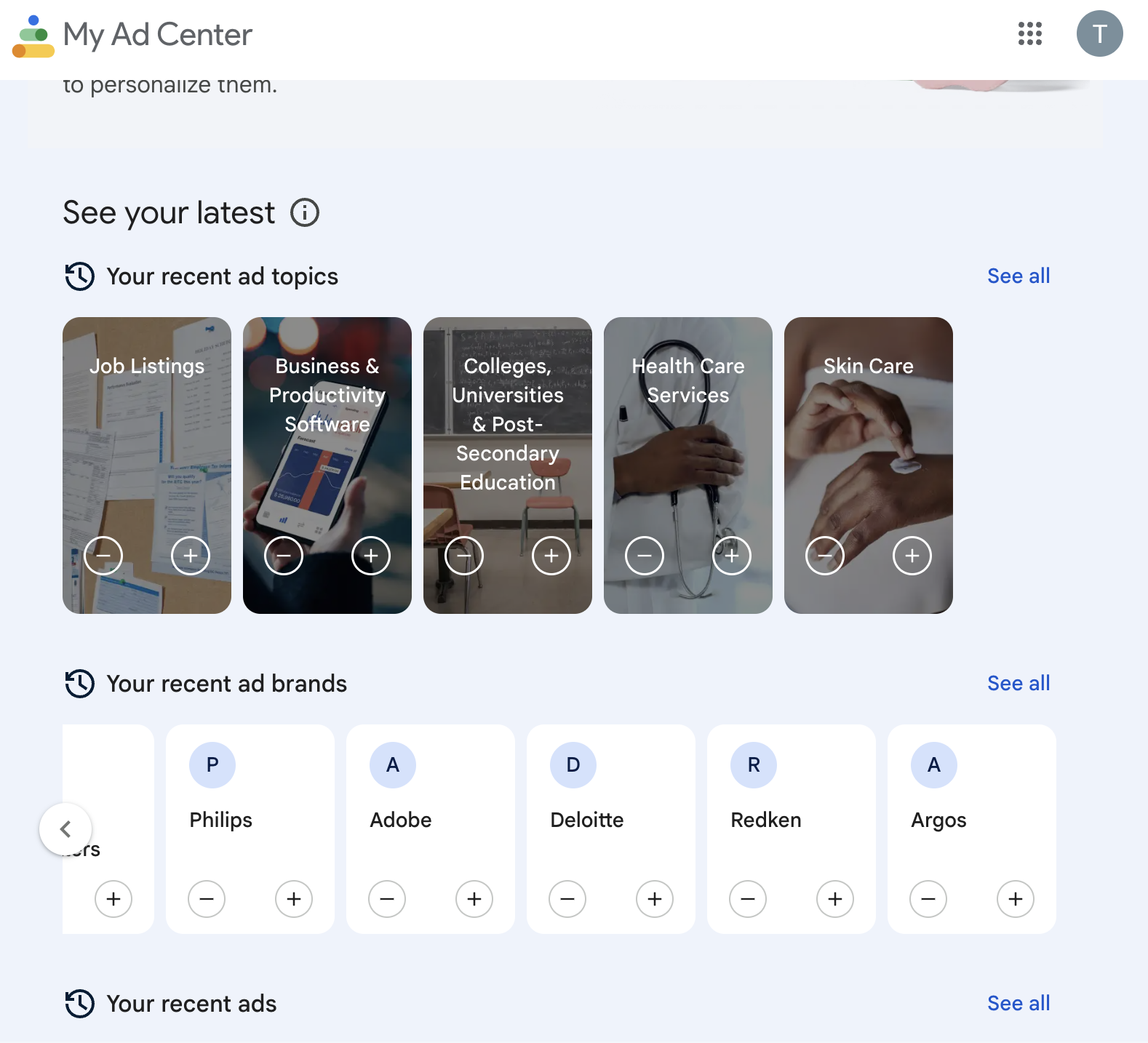

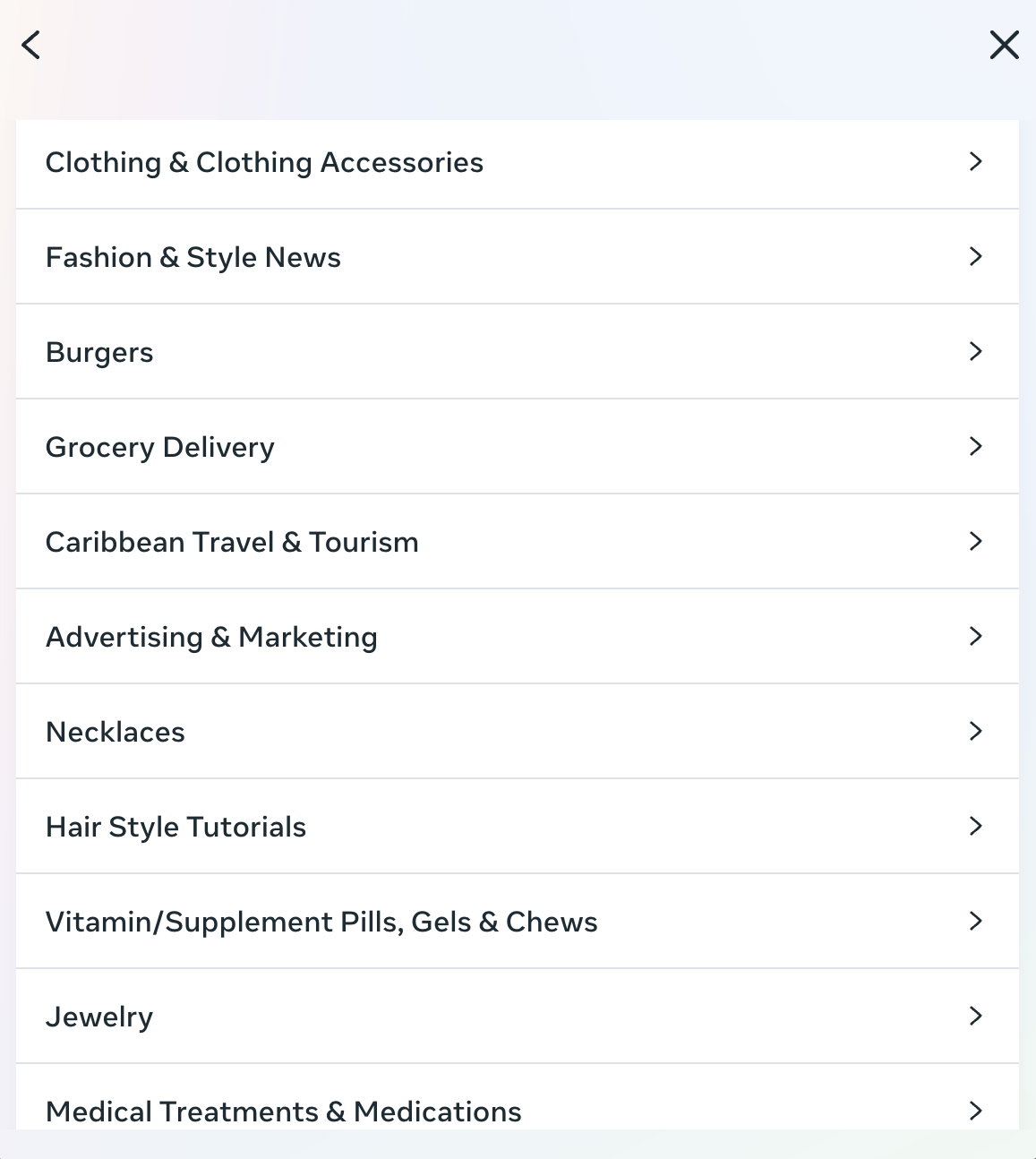

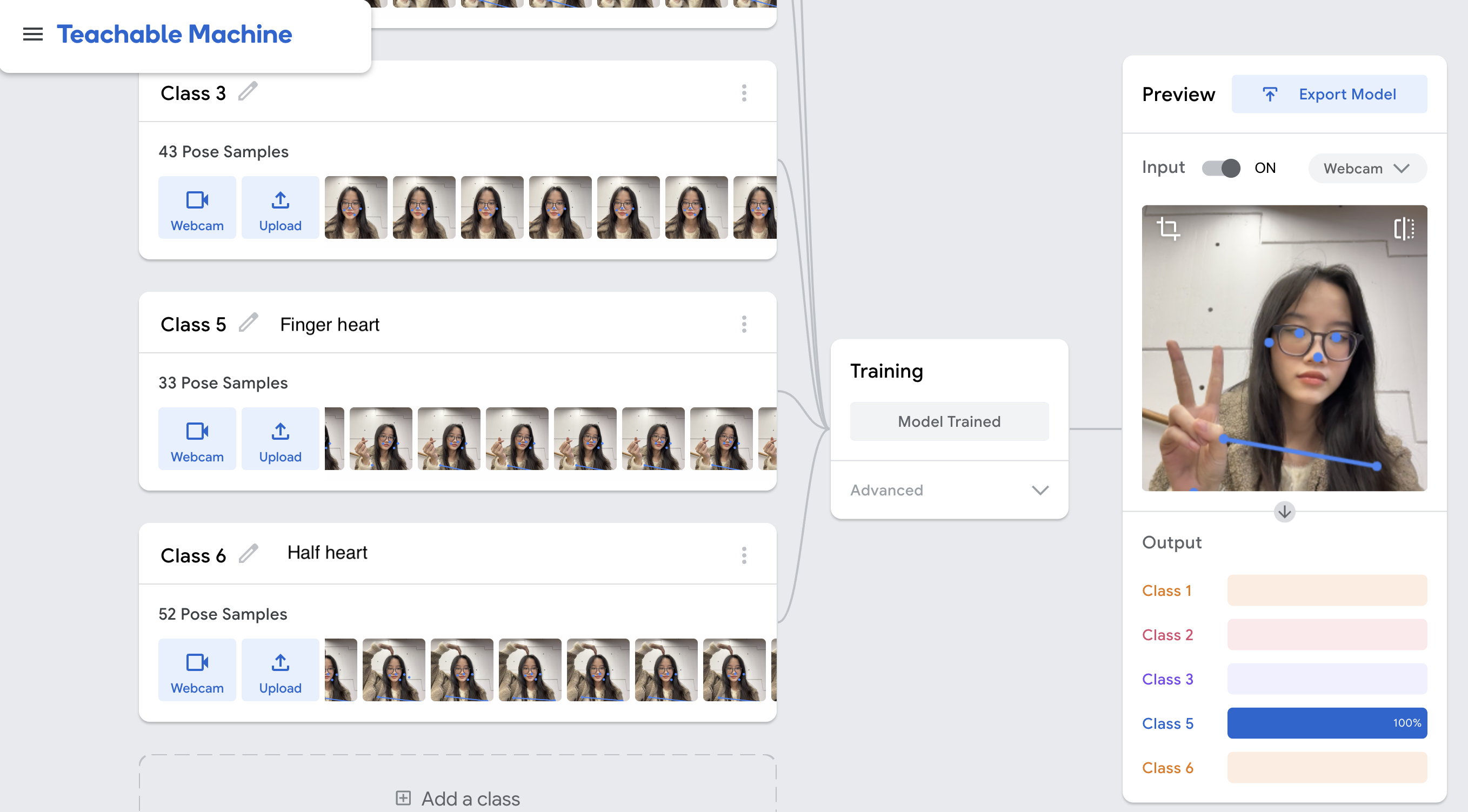

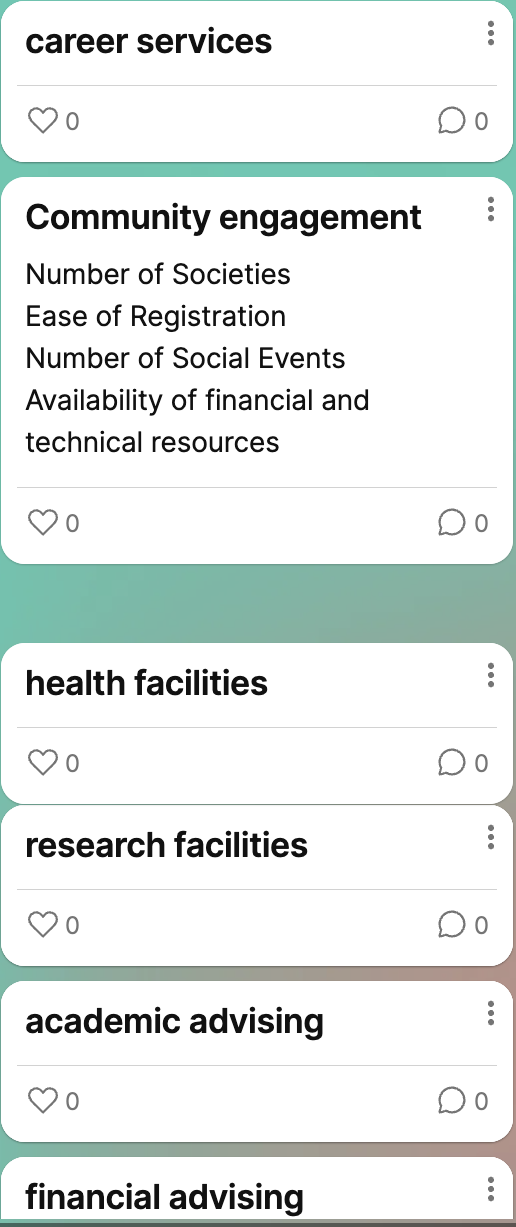

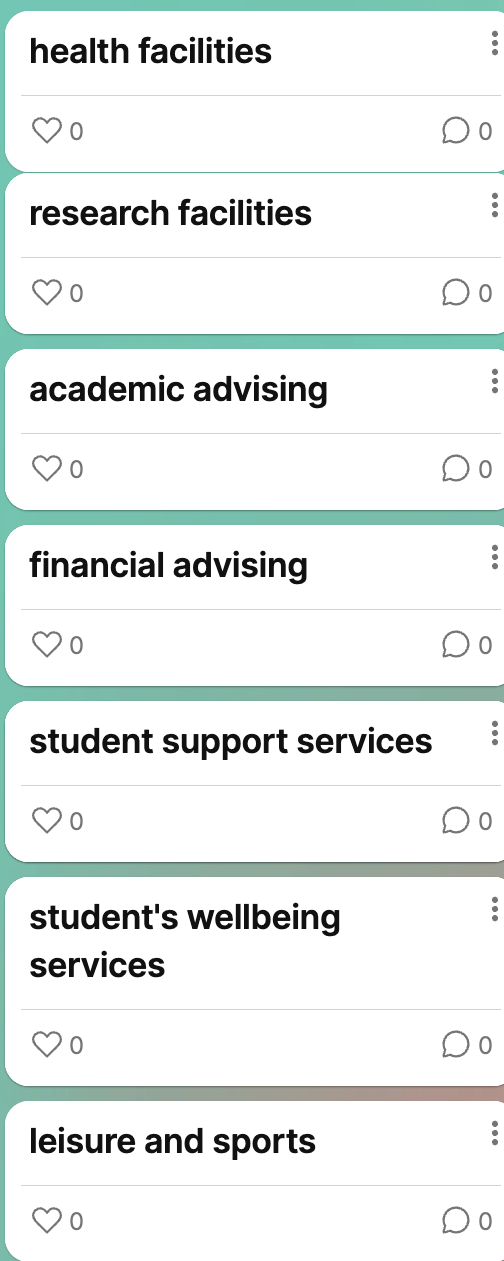

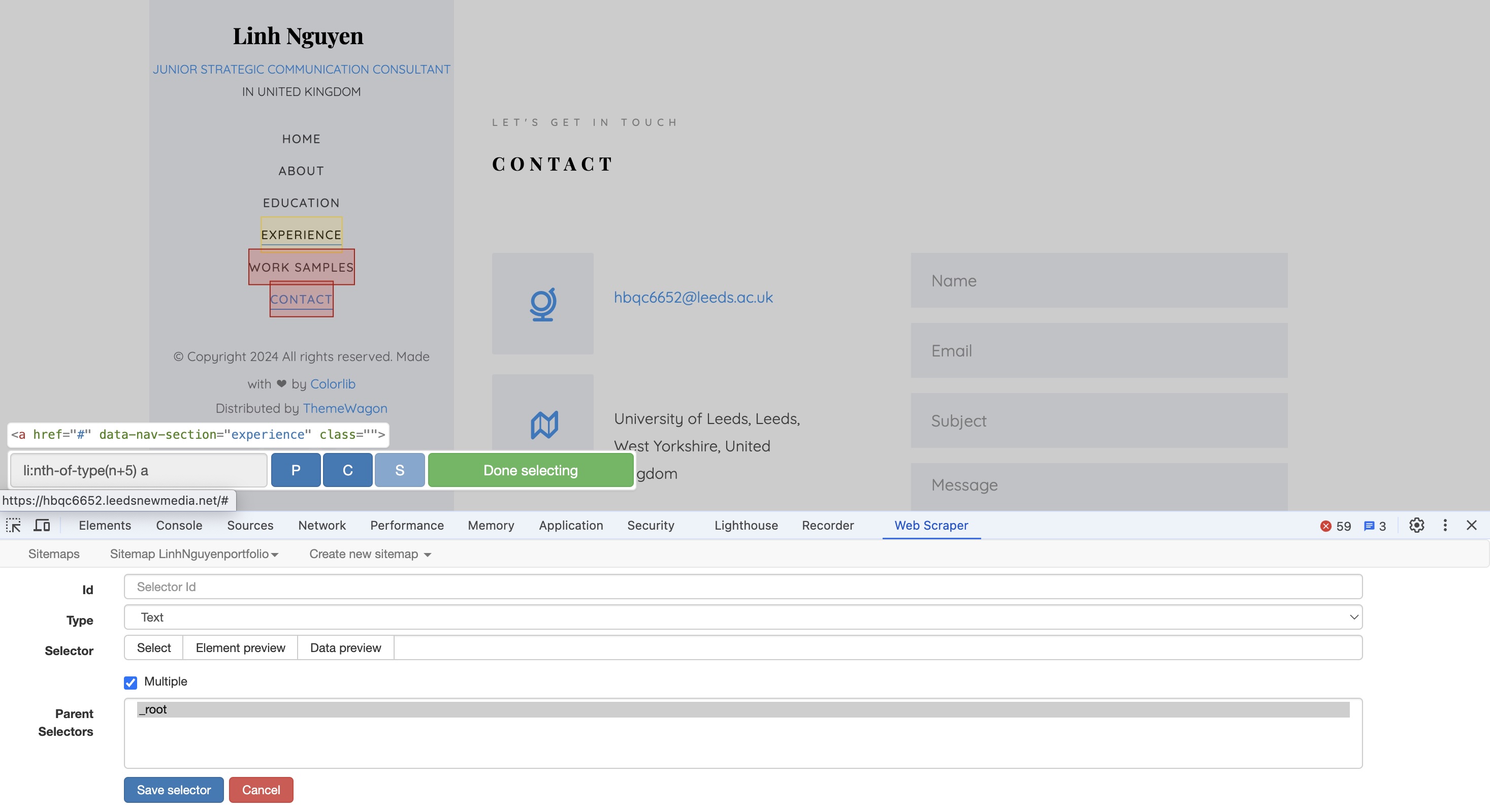

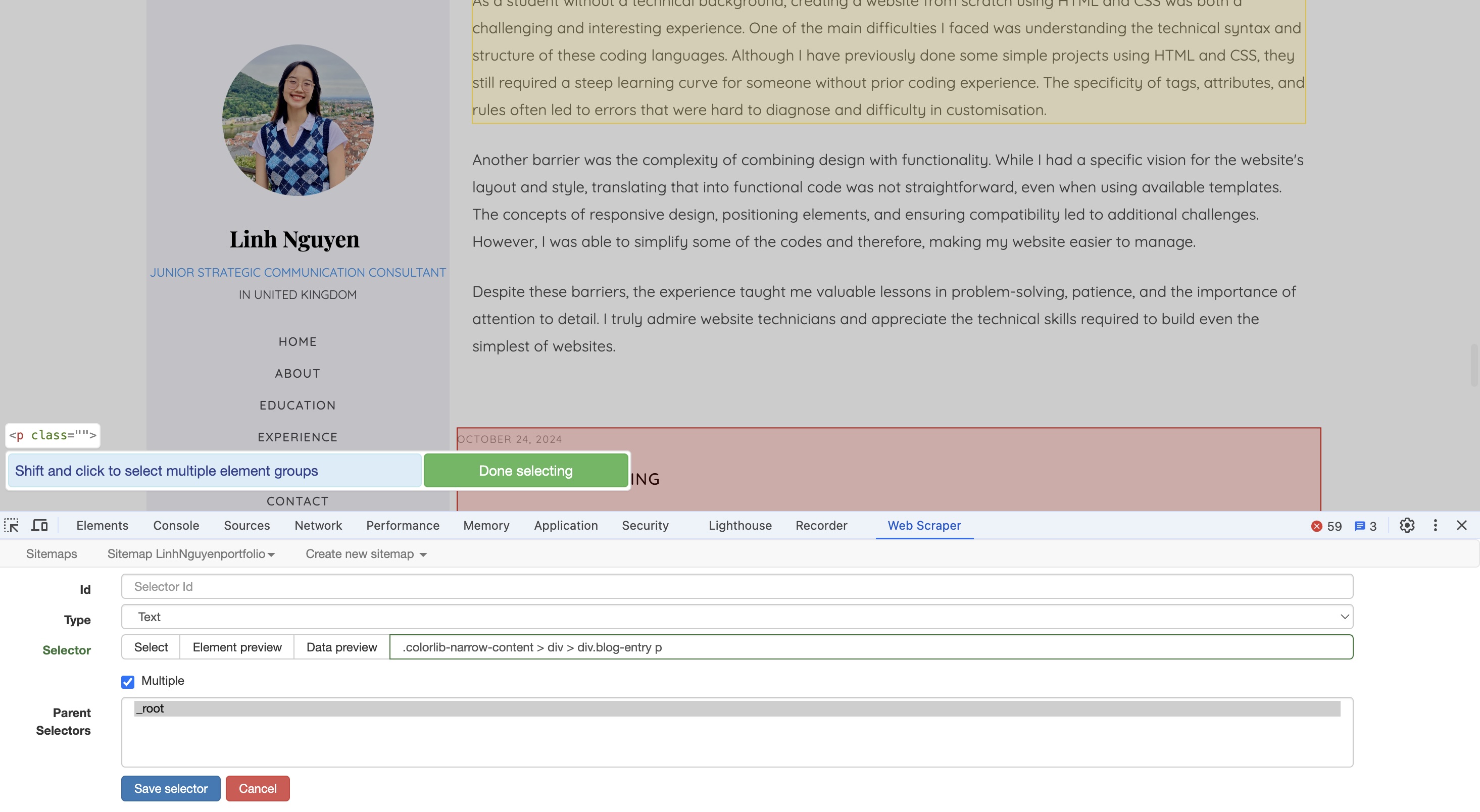

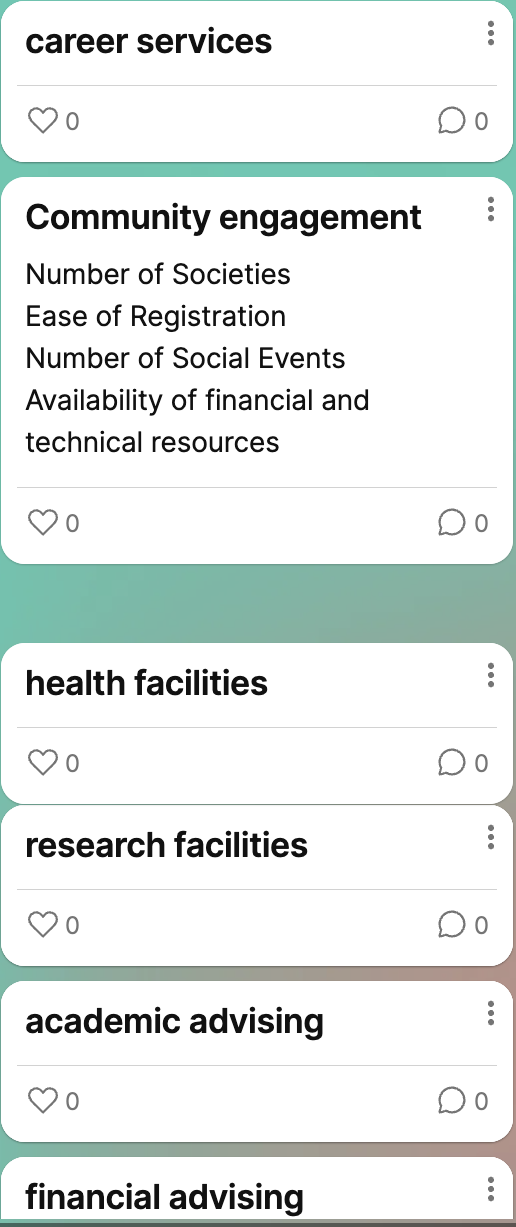

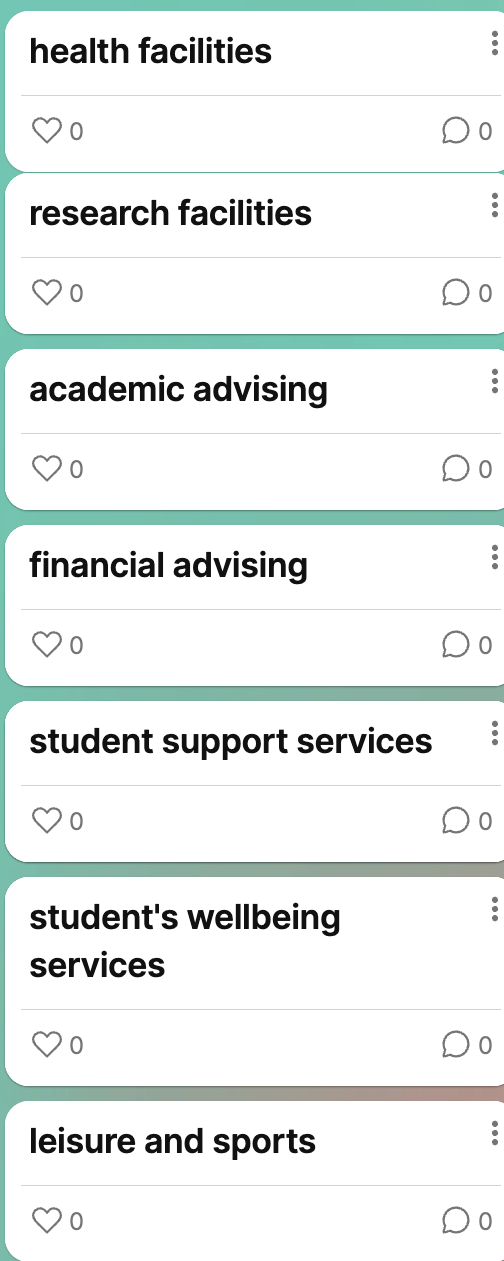

Working through this workshop really opened my eyes about the complexities of data collection and classification. One thing I learnt was the importance of clearly defining the scope of our research. For instance, when collecting data on the student experience, we listed out all of the aspects that would fall into the umbrella of “student experience”, from academic resources, employability or career resources, financial resources, to community engagement,... (see IMG 4.1 & 4.2). Now the availability of resources that prompted us to choose this scenario became a problem: how can we narrow down our focus?

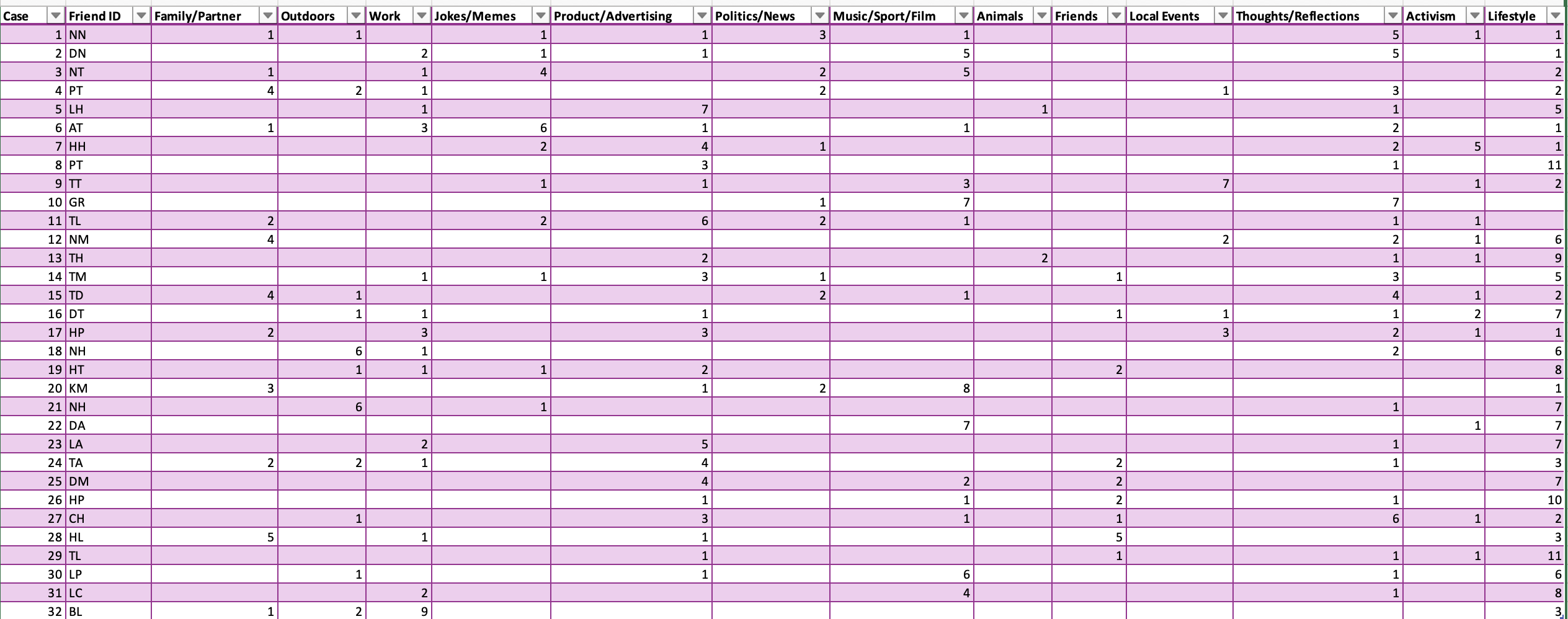

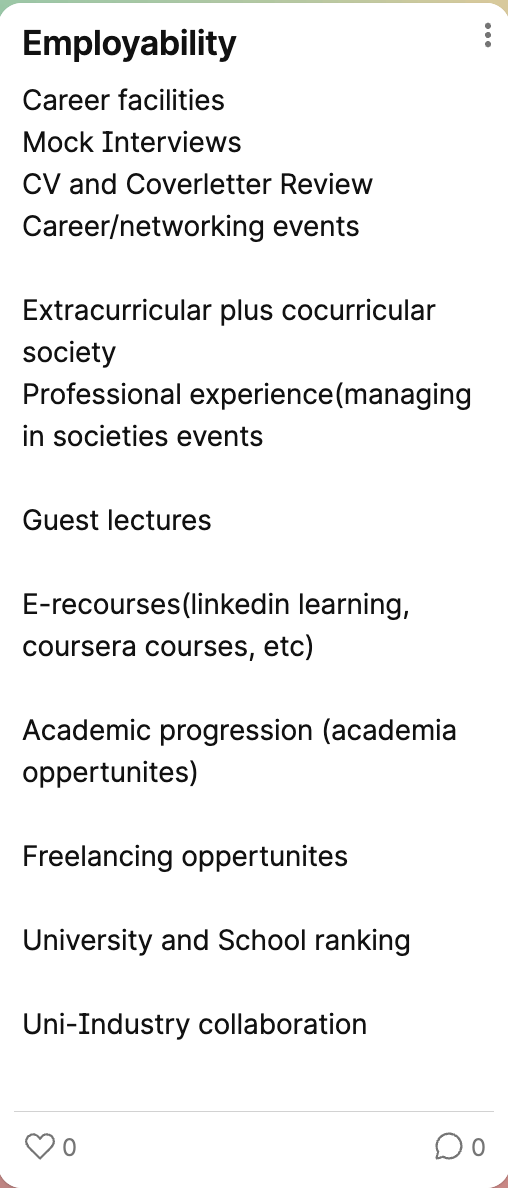

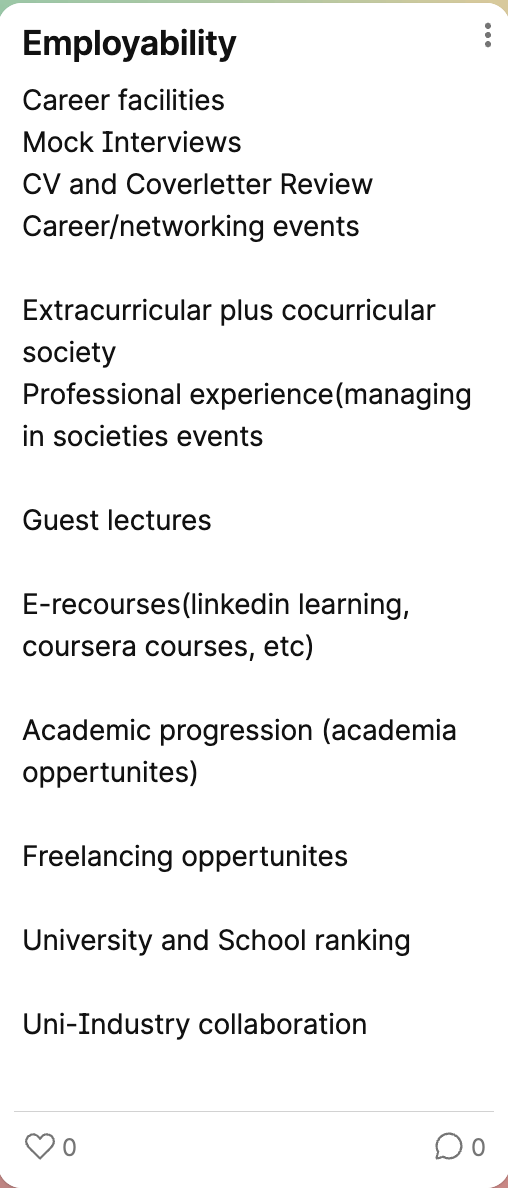

To further refine this focus, we brainstormed and listed various aspects of employability (see IMG 4.3). However, even with this narrowed scope, we realised there were still too many options to analyse. Our attempt felt futile as the breadth of potential subtopics continued to challenge us. I finally understand what Crawford (2021) meant when they wrote: “From the outset, data was characterized as something voluminous, disorganized, impersonal, and ready to be exploited.” (p.107) Employability data, for example, is seemingly straightforward, yet it quickly becomes overwhelming to us due to its volume and the interconnectedness of its elements. It is easy to overlook the complex labour and critical thinking required to process and interpret data meaningfully. Our struggle to make sense of employability data proved the tension between the messy, multifaceted reality of human experiences and the oversimplified way they are often represented in data visualisation systems.

Then, Holly visited our table and, after listening to our explanation, suggested that we focus on collecting employability information from the program prospectus, including employability rate, availability of career fairs and workshops, etc. She recommended including five programs from the School of Communication and Media. This guidance gave us a clearer understanding of the specific type of data we should prioritise.

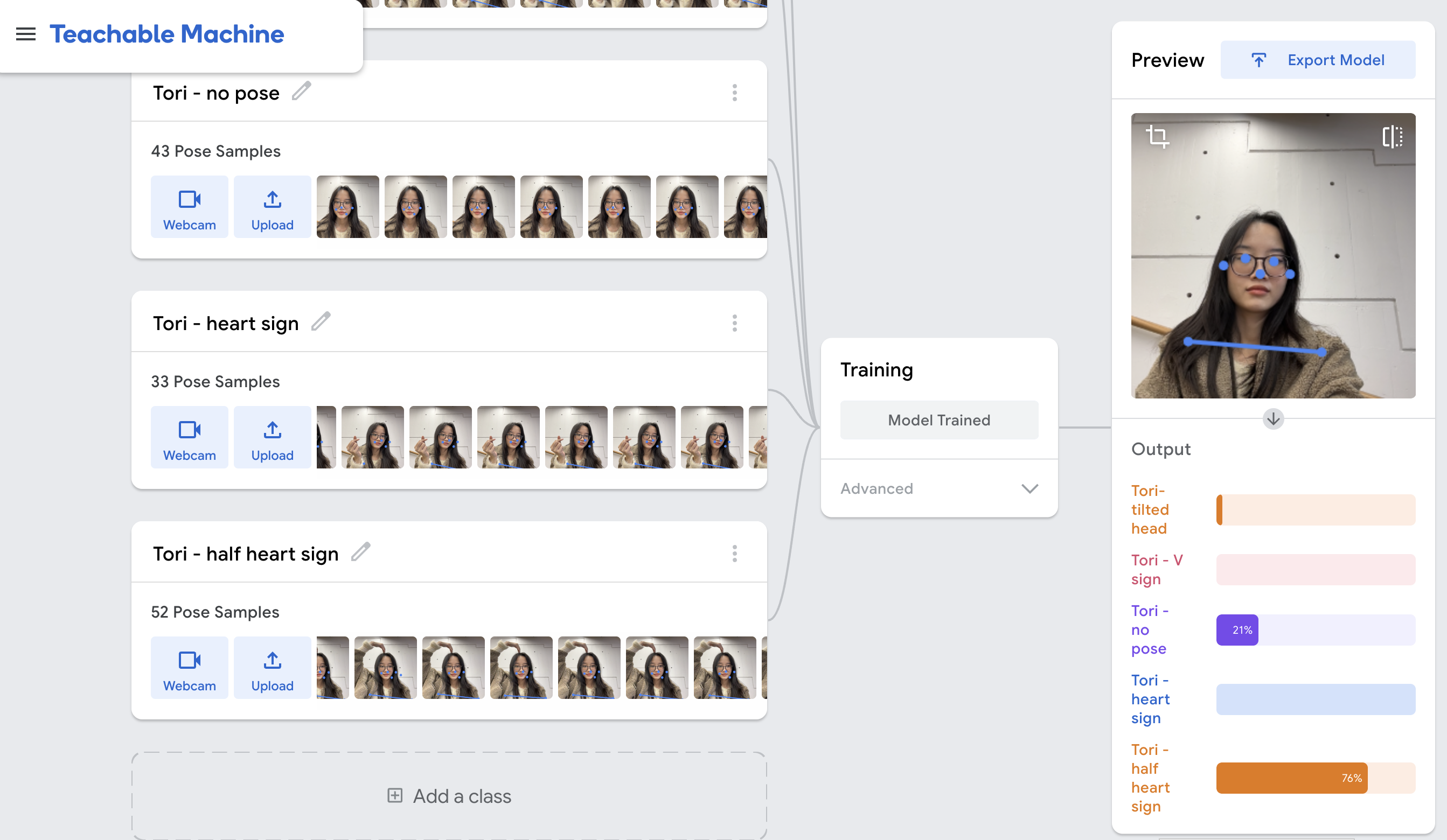

This experience has made me reflect deeply on how data, specifically, the data generated from our everyday activities, is gathered and labelled. While supercomputers can now generate massive amounts of data in less than a second, the task of labelling still heavily relies on human labour. As Crawford (2021) highlighted, the practice of labelling large datasets is often outsourced to crowdworkers who are severely underpaid for what is considered manual labour. But is labelling data really as straightforward as it seems? Based on our experience of constantly brainstorming, listing, focusing, refocusing, and narrowing down in the workshop, I find it hard to believe that labelling data is a simple task. The nature of human experience itself is inherently multifaceted and deeply context-dependent. Who gets to decide which label is appropriate for a given piece of data, and what criteria guide these decisions?

Reference:

Crawford, K. 2021. Data. In: The atlas of AI : power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 89-122